After focusing on objects and materiality for a bit, this week I returned to the library to read texts. It struck me once again how dense very small pieces of text can be. Part of my new project on metals in Boerhaavian chemistry is getting an idea of how popular and academic medicine worked in practice before Boerhaave. To this end, I am reading late seventeenth-century chemical and pharmaceutical handbooks. From just the two-page foreword of a Dutch 1667 ‘Galenic and Chymical’ pharmaceutical handbook, I could derive the so much about how a seventeenth-century pharmacy functioned, that I want to share it with you.

This handbook is a bit of an exception as it is Dutch, while most chemical and pharmaceutical handbooks of the time were in Latin. But although apothecaries were generally expected to understand Latin, in practice this was not always the case. Unlike today, an apothecary did not need a university degree to practice, and most learned their trade as an apprentice after a couple of years at school. This education system made perfect sense to the author of the handbook, as many of the common ‘compositions’ made by the apothecary were not described in any book: making them was tacit knowledge, not even transferred from master to apprentice orally, but through demonstration and doing.

As a sort of supplement to this very practical training, this particular handbook was aimed at young student-apothecaries, and advised them to make sure they learned the Latin names of all the Simplica and herbs (base ingredients) by heart. The author – a Jesuit apothecary – suggests several ways in which this could be achieved: by keeping a list of all the simplica supplied by the druggist and frequently pouring over this, by studying herbaria and other books, by regularly checking the written signs in the apothecary garden, and by looking up the herbs brought in by the ‘herb-fetchers’ (Kruydt-haelders) in books and marking them appropriately after drying.

From this advice, we can deduct a number of other things, like that the apothecary and his apprentice were part of a professional network consisting of at least a druggist and a herb-fetcher. The herb-fetcher is described as getting all the herbs growing in the wild for the apothecary in the cities, and the druggist functioned as a sort of whole-seller of base ingredients for the apothecary. The text also indicates that an apothecary generally had his own herb garden and books, and combined with the fact that he needed to understand at least some Latin, this made the profession a quite respectable one.

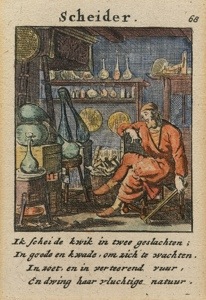

We still tend to think of apothecary as a quite respectable profession, but by no means do we think of the apothecary and the alchemist as closely related professions. Yet in the seventeenth century they were: the title page of this handbook reads ‘Galenic & Chymical Pharmacy, That is: Apothecary and Alchymist’ (Pharmacia Galenica & Chymica, Dat is: Apotheker en Alchymiste).

Source: Bisschop, Jan. Pharmacia Galenica & Chymica, Dat Is Apotheker Ende Alchymiste Ofte Distilleer-konste : Begrijpende De Beginselen Ende Fondamenten Der Selver. Verdeylt in Acht Boecken, Tot Onderwijsinge Der Apothekers / Door Een Liefhebber Derselver Konste Nieu Licht Der Apotekers En Distilleerkonst. Antwerpen: Reynier Sleghers, 1667.

You must be logged in to post a comment.